What does it mean to be an American?

We are finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation. This #nprnextgenradio project is created in Oregon, where four talented reporters are participating in a week-long state-of-the-art training program.

In this project we are speaking to people from various walks of life—whether they are Indigenous, native born, a naturalized citizen, a refugee or an immigrant without legal status—to ask what it means to be an American.

Charlotte Powers interviews a formerly incarcerated man in Portland who’s been evaluating how his American identity changed while serving his 13-year prison sentence.

Illustration by Lauren Ibañez

Regaining freedom to choose: Formerly incarcerated man prioritizes family, forgiveness and self-determination

Sitting at the kitchen table at his in-laws’ home in Lake Oswego, Oregon, 53-year-old Steven Stroud said his American identity vastly changed while serving his 13-year sentence.

Stroud’s rough upbringing kept him from thinking about what it meant to be an American.

He entered the foster care system and was placed in King County, Washington. Stroud was repeatedly bullied because he was a white child in a black neighborhood.

Steven Stroud spots the light after years of darkness

“All I understood was these people who looked different than me were attacking me and hurting me and I didn’t understand why because I had done nothing wrong to them,” Stroud said.

When he was 12, Stroud was attacked outside of a nightclub when a bald man wearing all black and boots came to his defense.

“[The man] took this guy off of me and kicked the living hell out of him,” Stroud said. “He then bought me some food and sat and talked with me. … I got my first indoctrination into skinheads. I found that hanging around them kept me safe.”

Stroud embraced racist doctrines his entire adolescence; but in his early twenties, he began to question them. He realized that the discriminatory practices he condoned were no different than the reasons his childhood bullies utilized.

Stroud unlearned the racist teachings he grew up with and decided to help other skinheads in Portland unlearn these same beliefs.

Stroud’s actions caught the eye of a professor at Portland State University, and together they created Oregon Spotlight, an organization that conducted outreach to white nationalist youth and helped deconstruct their racist values. For Stroud, Oregon Spotlight was also an opportunity for self-growth.

“As I began to understand more of who I was, that began to help me understand my country, help me understand the geography and the morals and values that I lived around,” Stroud said.

In addition to collaborating with Oregon Spotlight, Stroud worked as a security guard for private institutions and bars. While working at a hospital, a patient bit into Stroud’s kneecap, tearing his meniscus and tendons. Stroud was prescribed Oxycontin.

“I was told it was completely non addictive and harmless,” he said.

Once pharmaceutical companies were aware of Oxycontin’s addictive properties, they restricted the drug’s distribution. Stroud was able to purchase the drug for a short time, but the escalating price was not sustainable. Working at a bar one night, Stroud was going through serious withdrawal and someone offered him heroin.

“I embarked on this heroin spree,” Stroud said. “I finally realized that this is what it’s like to be addicted.”

Stroud attempted to get clean multiple times but failed.

“I became suicidal,” he said. “I didn’t have enough guts to kill myself. … I was going to have a cop do it.”

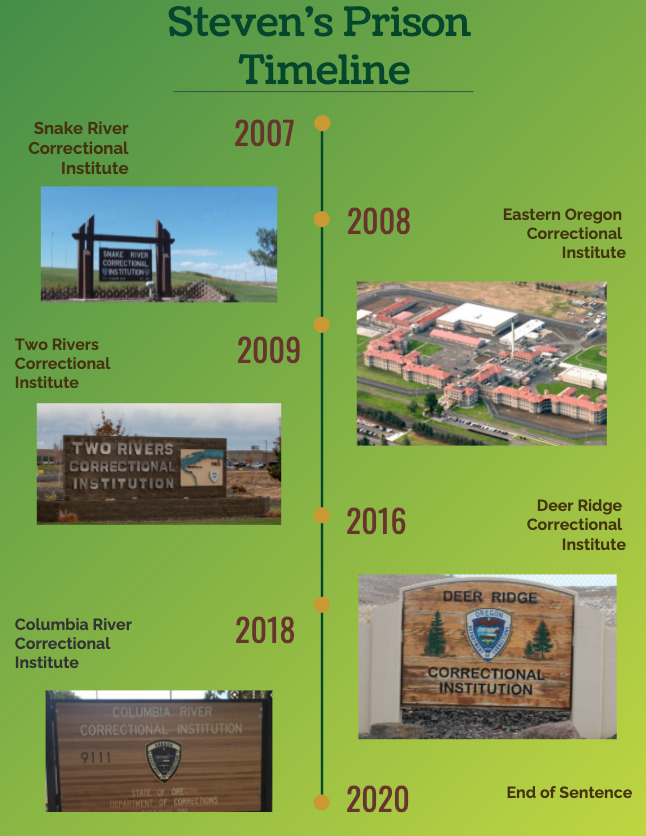

Stroud committed a series of robberies and was caught in 2007.

Before arriving to prison, Stroud always saw officers as allies, but he quickly understood this image was a facade. Stroud’s 13-year sentence showed him how officers work to deprive prisoners’ rights, rather than uphold them.

“I believe that my rights as an American didn’t exist inside prison. The people wearing these badges and American flags on their arms, [who] were looked at as heroes, were the same people that were now being brutal and oppressive behind walls and couldn’t be seen.”

Steven Stroud sits at the kitchen table at his in-laws house. Stroud recently got engaged to his fiancee, Donna, following his release from Columbia River Correctional Institute. (Photo by Meerah Powell)

Upon his release in June 2020, Columbia River Correctional Institute neglected to give Stroud an I.D., food stamps and the money he saved while working in prison.

After leaving the jail, Stroud noticed tents and garbage in the street, which is something he was not used to seeing before his incarceration. He said he realized there was no assistance available for him or these other people.

“Sure COVID may have been affecting some things and obviously was. But I became very aware that the country I had left was not the same America I was walking back into and oppressive forces were more in control now than they had been before,” Stroud said.

Still, Stroud said he is proud to be an American because of self-determination, an intrinsic American quality.

In just a year after his release, Stroud is now employed, has remained sober and is engaged to his fiancee, Donna.

“One of the things that I found in freedom was acceptance and love from a family, which is something I have never had. And I had the freedom to do that as an American,” Stroud said. “You just have to realize that that power lies within you. Our country provides a nice backdrop for that, but it’s not the end-all be-all of life. I believe that everybody can do what I did and experience the happiness that I currently experience.”

Wearing a black sweatshirt, Steven Stroud poses with his fiancee, in-laws and two Beagles in their backyard. Stroud remarks on his love for his newfound family and how they welcomed him into their home. (Photo by Meerah Powell)